I’m still thinking about the issue of relevance in the teaching and preaching of the Bible in our churches. The sad fact is, “relevance” is actually most often simply a code for “popularity.” A speaker who riffs on the biblical text with stand-up humor, zinging one-liners, and a few pulls on the heart-strings, will be applauded as “making the Bible come alive” or “making the Bible relevant” when they are often just using the Bible as a pretext to entertain people. The message isn’t coming from the text, through the speaker, but the speaker is using the text for her or his own purposes. These purposes might well be lofty, but in the end, it’s an appeal to the gallery, to popularity.

I mean, why should we do the hard work of drilling down into the biblical text, using the tools of exegesis and criticism systematically to strip away our own agendas until we are so confused and turned around, we lose track, however briefly, of what we thought the text was supposed to mean, and we stumble straight into what the text actually does mean. Why would we do that when jokes, one-liners, sentimental platitudes, cheap appeals to popular prejudice and a heart-rending story or two are easy enough to find!

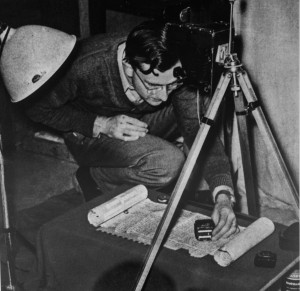

Believe it or not, that biblical manuscript at the top of this page is about that. It might look familiar. I used it a couple days ago for another blog. Hang in here with me, this’ll make sense in a minute.

It’s a fascinating manuscript. Let me tell you about it. Before Christianity was born, Jews had already realized that God did not “speak Hebrew” but in fact, his word could be translated into other languages and still be his word. Of course, as

in any enterprise of translation, the original remains the touchstone of the text’s integrity, but still, Jewish thinkers realized that the eternal word of God could inhabit any language, and that translation not only was possible, it was vital.

As a result, scholars in the centuries prior to Christ translated the Hebrew Bible into Greek, ultimately (long story) producing what came to be known as the Septuagint, abbreviated LXX. The early church took for granted, right from the beginning, the Jewish confidence in the divine word’s “translatability” and employed the LXX along with other Greek translations. About the time the Greek OT hit its peak in popularity, the world begin to speak LATIN. Many in the church resisted Latin, thinking that the Greek OT was “good enough for Jesus and Paul” so it’s good enough for us. Still, more and more preachers and teachers translated the Greek OT ad hoc into Latin. Some were skilled and knowledgable, some were mediocre, some absolutely awful, so that a translation tradition known as the “Old Latin” became both beloved, but also lamented, for its inaccuracies and internal contradictions. Ironically, though, most failed to see that the root of the OL’s instability was its reliance on the Greek, a translation which itself had been revised, altered, messed up by copiest errors, and riddled with problems.

Something had to be done.

So a scholar Jerome was called upon in the decades around AD 400 to produce a standard, reliable Latin Bible. As Jerome worked, he realized Greek manuscript tradition was more tangled up than a 9 year old boy’s fishing line. Being a translator of great skill, Jerome knew that the answer was to translate not from the Greek, already one step removed

from the original, but to use the Hebrew text. This proved controversial, and merits its own post (later!). Eventually, Jerome’s Vulgate became the standard Bible of the Church for about 1000 years, which is not a bad run by anybody’s estimation. We OT scholars treasure Jerome’s Vulgate because we actually don’t have a lot of information about the text of the Hebrew Bible in the era between Jesus and the rise of the “official” masoretic text about 1000 AD. But Jerome’s latin, based on the Hebrew text of his day (ca. 400 AD) often gives us priceless clues as to the wording of the Hebrew text in this “dark age” of Hebrew text transmission.

But I digress…

Of course, the church did it again: they’d stuck on the Greek, then about the time they admitted the need to translate from the original into Latin, they got stuck on the Latin! Over the centuries, Jerome’s translation suffered errors of scribal copying, well-intended but inept corrections, expansions, improvements… so that we sometimes don’t even know what Jerome actually wrote, so the value of his translation for its insight into the Hebrew text is quite obscured.

Now, to my manuscript! Working on the book of Judges, I was delighted to discover that the oldest known manuscript of the Vulgate version of any OT book happens to be a copy of the Vulgate book of Judges! This manuscript, known as the Bobbienser Palimpsest, dates from the mid-5th century, or just a generation or two later than Jerome himself! It’s a beautiful manuscript, featuring a fine uncial (all capital letters) hand.

Now here’s the sad part. Apparently some centuries later, the Bible wasn’t as important to people as some other books. Apparently some other books seemed more relevant, more useful, more practical and certainly more popular than the Bible. One of those was a massive Christian “Encyclopedia of Everything you Need to Know and More” kind of a medieval wikipedia-home-school curriculum all the way up to the PhD, compiled back in the early 7th century by a guy named Isidore of Seville (the one in Spain). I’m not knocking Isidore, Seville, Spain or even his encyclopedia (called Etymologies) except that in their wild rush to get more copies of Izzy’s stuff out there to a waiting public, scribes started wiping the writing off of older texts they didn’t need anymore and just writing Isidore’s on top. Scholars call these manuscripts palimpsests, and literally one text is written on top of another, which is usually partially or completely erased.

So you’d think they’d use old useless stuff for this re-copying, but alas, at some point this precious, almost straight-from-Jerome copy of the Vulgate Judges, got commandeered. Judges was wiped off, and is almost invisible to the naked eye. On top, in a cramped little minuscule Greek hand, is written portions of Isidore’s Etymologies. Who needs the Bible when you’ve got Isidore? Isidore was more popular, more practical, more in-touch with what’s happening, more…relevant. So the words of scripture fell into the background and the words of the encyclopedist, admittedly a godly and brilliant man, came literally to the foreground.

Every time I study this work, I think that in many ways, this manuscript is a parable of the modern church. For whatever reasons, the actual words of scripture fall into the background, even get erased or dimmed, and more contemporary voices come to the front. Why read a dusty old biblical text when we can read the All-In-One Guide to Total Learning?

Enter Alban Dold, one of the most seriously sick Bible-geeks who ever cracked a scroll, though it’s doubtful he ever got a suntan or heard rock-n-roll. In 1931 this German scholar, employing some super-slick (for 1931) lighting and photographic techniques, restored the lines of the near-obliterated biblical manuscript. Suddenly, Jerome’s Judges re-emerged. And what’s funny about this is that today, unless you’re a church-history geek, you have no idea who Isidore of Seville is, nor do you care. He was a rock-star in AD 700, but today, not even a memory. But Jerome, his contribution to the principles and practice of Bible translation, and his priceless Vulgate, remain cherished and treasured in the church.

In the end, ill-tempered and pretentious, moody and contentious St. Jerome, hulking in his cave in Bethlehem, brooding over Hebrew and Greek texts, agonizing over the best Latin idioms, absolutely nuked Isidore for continuing relevance. Thanks to almost cultic ally obscure people like Alban Dold, Jerome continues to challenge us to a constant return to the text of scripture, in the original languages and contexts, as the one and only source of life and light, the one thing that is always authentically relevant.